|

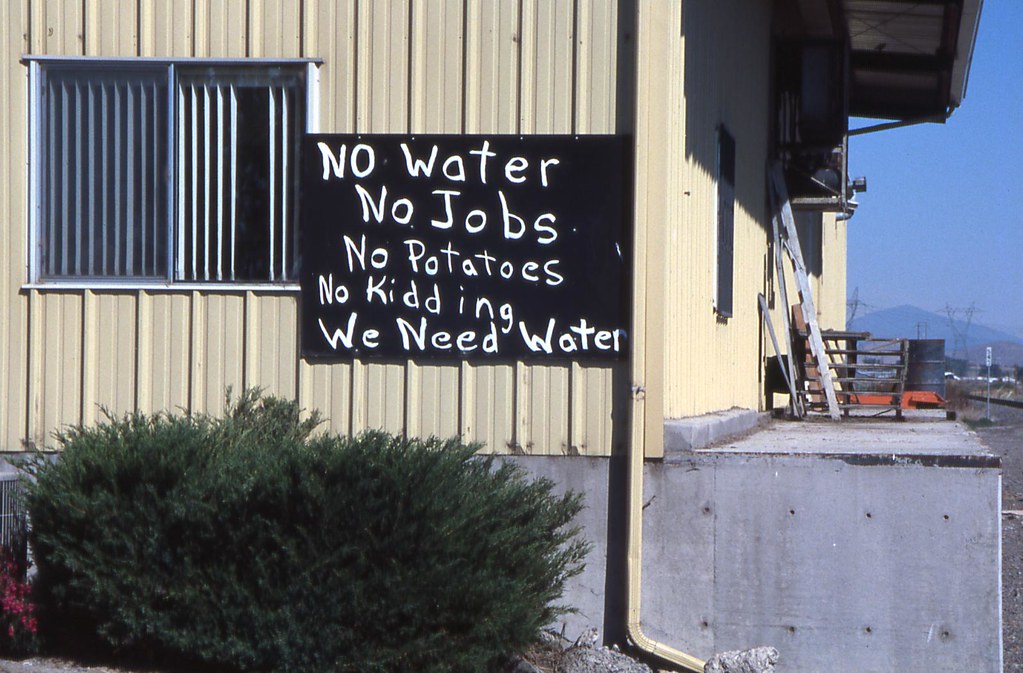

| Source:Oregon Department of Agriculture via Flickr |

Both the state of California and several cities in Taiwan have issued water rationing in the last few weeks. A quick google search will tell you that these two places are not alone in the fight against droughts – in fact, some parts of Africa and South America are facing the dire water shortage problem as it threatens the people’s basic livelihoods. In São Paulo for example, the economic heart of Brazil, the word ‘water refugee’ has emerged to describe population relocation as a result of droughts.

Although a certain degree of drought can be attributed to meteorological cycles, the persistence, severity and inconsistencies of droughts across the globe, is without a doubt, a product of anthropogenic climate change. Nevertheless, there are country-specific problems that have led to not only the inevitability of drought, but the exacerbation of it.

In the case of the west coast of the United States, the state of California relies on snowpacks as their primary source of surface water such as streams and lakes. However, this year marks the fourth consecutive year that California’s snowpack is below normal. When surface water falls short, groundwater is drilled to make up for the difference. Last week for the first time in history, Governor Jerry Brown of California issued to reduce water use by 25% - the biggest skepticism with this executive order is that, though the agricultural sector consumes the majority of water, it remains the only industry that is exempt from the latest rationing.

|

| Snow in the interior of Nevada on March 27, 2010 Source: The Earth Observatory/NASA |

|

| Snow in the interior of Nevada on March 29, 2015 Source: The Earth Observatory/NASA |

When faced with extreme resource scarcity problems, especially as they pertain to one of the most essential elements that sustain life – we ask ourselves why and how we brought this to humanity in the first place? And more importantly, is there a way out of the downward spiral? Indeed, national policies could be refined so that reservoirs can operate more efficiently; water pipelines could be repaired to reduce leakages. Yes, water prices should go up to more accurately reflect the real cost of utilizing water as a natural resource. And yes, people’s behaviors need to change, and water conservation should be rooted in their daily activities. These are some of the most critical and logical steps to tackle the global water crisis, one step at a time. However, we cannot but start addressing the elephant in the room – that is, the fundamental driver that led to extreme weather events, where drier places are subject to severe droughts, and wetter places are exposed to intense floods – namely, anthropogenic climate change.

Many have come to the conclusion that climate change is not a technological problem, nor is it an economic problem – however, it can be viewed as a behavioral problem. Why is that? The solutions below can all be traced back to behaviors – whether it is government behavior, the behavior of the free market, the educational system, or the behavior of any and every individual – the very paradigm we created is the problem to our water problem. And here is how we can change that.

|

| Source:UN Photo/Albert González Farran via Flickr |

On a more personal level, we can start water conservation by pledging to take 5 minute showers, limit car washes, or removing grass lawns and replace them with desert plants. To take this to another level: one could retrofit laundry machines so that the used water can be reused to water drought-resistant plants, for example. Finally, let us be reminded that it does not seem all too impossible now to contemplate on the idea that wars this century will not be fought over oil, but over water. If we act now, we can still reverse that reality.

Further Reading

California's Drought Page

US Drought Monitor

沒有留言:

張貼留言